First in Southeastern Public Schools …

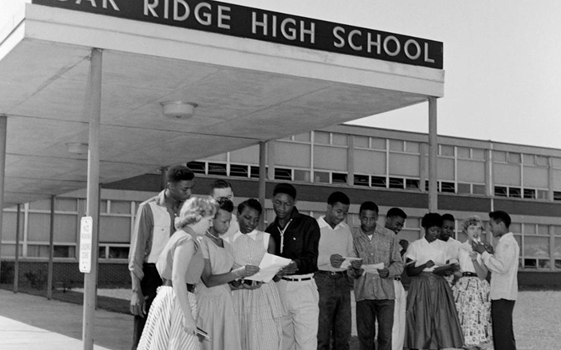

Despite the tragic murder of Emmett Till only two weeks before, eighty-five brave Black students from the segregated neighborhood of Scarboro quietly entered All-White classes in Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High School in Oak Ridge, Tennessee — in Anderson County — on September 6, 1955.

They were the very first to challenge the color barrier in public education in the Southeastern United States — a dangerous path for these courageous students, parents and teachers.

Oak Ridge was a “Secret City” created by the Manhattan Project in rural Tennessee during WWII, It was totally-segregated during the war.

Housing, buses, churches, stores — and everything else — was racially segregated. Severe economic and criminal penalties faced any Black MP worker who broke any of these invisible racial boundaries.

One of the key racial restrictions was that Black children were not allowed to spend the night within the city during the war — unlike White children.

Black parents could only see their children for brief periods during the day. On the other hand, White MP parents were allowed to bring their children intoi the city and were provided (by the federal government) with one of the finest school systems in the state for their children

Black workers were housed in the lowest-level housing that was separated by gender, regardless of marital status. Male and female housing was maintained under prison-like conditions, with guards able to enter at will. In contrast, White workers were provided with a variety of married housing options in open neighborhoods.

Despite these rigid racial beginnings, in January 1955 the Department of Energy (then the Atomic Energy Commission) ordered the City to desegregate its public schools. This overruled a local public vote, which lobbied for the continuation of school segregation.

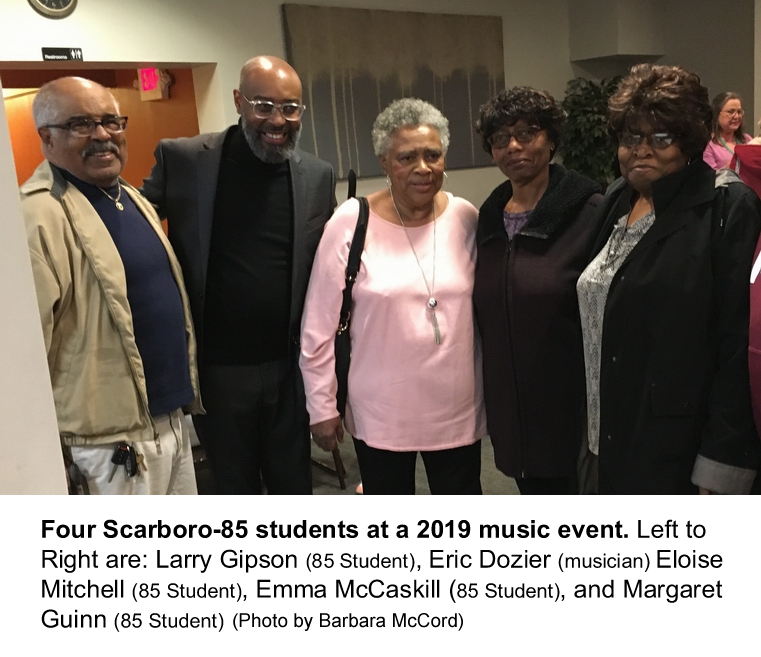

Then in September 1955, eighty-five brave Scarboro 85 students provided America with its first major victory over the Jim Crow racial culture — when they quietly desegregated the local public schools. At the time, the Tennessee state constitution (like other Southeastern state constitutions) expressly forbid mixed classes.

This game-changing moment in American history was an amazing achievement for the Scarboro community, the people of Oak Ridge, the American nuclear industry — and for the entire nation.

Back in 1955, The Scarboro 85 School Desegregation Occurred:

1. Five years before Ruby Bridges entered public schools in New Orleans,

2. Two years before the Little Rock Nine,

3. A year before the Clinton Twelve,

4. Several months before Dr. Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks rose to national prominence by leading the historic Montgomery Bus Boycott, and

5. Six years before the first three Black undergraduates were admitted to the University of Tennessee — (and fifteen years before the first Black UT basketball player!)

In 1955, the major question facing those involved with civil rights involved the reaction of the entrenched Jim Crow racial culture of the Southeastern United States. The trauma of the Civil War rested just below the surface in many Southern venues.

Would the South ever agree to dismantle its longstanding racial segregation?

Cultural separation of (freed) Black Americans stemmed back to the late 1700s. In the aftermath of the Revolutionary war, many slave-owners freed their Black slaves as a wave of egalitarian spirit swept the brand-new nation.

However, this freedom-giving practice raised troubling questions in the Old South with its very-large slave populations. How could someone viewed as a simple piece of property (a slave) — transform into a full citizen with all the rights of free-citizenship? What was the proper legal and economic status of these new citizens?

Suspicion quickly set in in the jittery South — and freed slaves were accused of encouraging runaways and slave discontent. A resulting wave of legal restrictions were enacted on: (a) the ability of slave-owners to free slaves and (b) the rights and priviledges of freed slaves.

Freed slaves were isolated from the general community as much as possible and subjected to severe limitations on employment. Their achievements and leadership were downplayed in an effort to convey that these Americans were somehow inferior.

Following the Civil War, racial separation continued under the legal fiction of “separate-but-equal” status — a view that concealed major economic and legal barrtiers faced by Black Americans.

Then World War II set the stage for a shift in this national view. Tradional racial roles throughout the nation, especially in the Southeast, were challenged by the great unity of the World War II effort.

Black Americans were affected by the trauma of the Pearl Harbor Attack — like White Americans. Blacks wanted to do their part to help win the war and pitched in. As a result, World War II began to slowly open doors-of-opportunity that had been traditionally sealed shut.

Eight years later, in 1953, the U.S Supreme Court began considering the issue for equal educational rights for Blacks. The stage was set for the modern civil rights era.

But how would Southeastern communities react? Who would be the first to challenge Jim Crow segregation in Southeastern public education? The answer came from an inspiring Tennessee community.